What is peering?

Why peer?

Network operators may peer for many reasons. Sometimes it’s cheaper to hand off traffic themselves rather than paying somebody else to do it. Sometimes it gives greater control over their traffic flows, or allows them to better serve local populations. If you’re paying EUR 10 per Mb/s per month, and somebody you are pushing 100 Mb/s of traffic to is willing to accept that traffic from you for free, you could save EUR 1,000 per month. In practice, things are not quite so simple, as the infrastructure required to peer also costs money, but that gives a basic idea.

Network operators who peer have more control over their traffic. If an operator sends or receives traffic over a transit connection, it goes across the Internet via whatever path the transit provider decides to use. If there’s a problem – slow connections or packet loss, for instance – the network is at the mercy of its transit provider. A network operator who peers has more control over external paths, and can easily adjust routing to avoid problem network segments. Peering can keep traffic local and improve performance. If a network’s transit provider has local connectivity, this may be moot. However, transit providers often cover large areas, and connect to other networks in few locations. If you buy transit in Stockholm, for instance, you may find that your path to another Stockholm network goes through London or Amsterdam. Peering can keep traffic local, providing faster connections between the two networks.

Types of peering

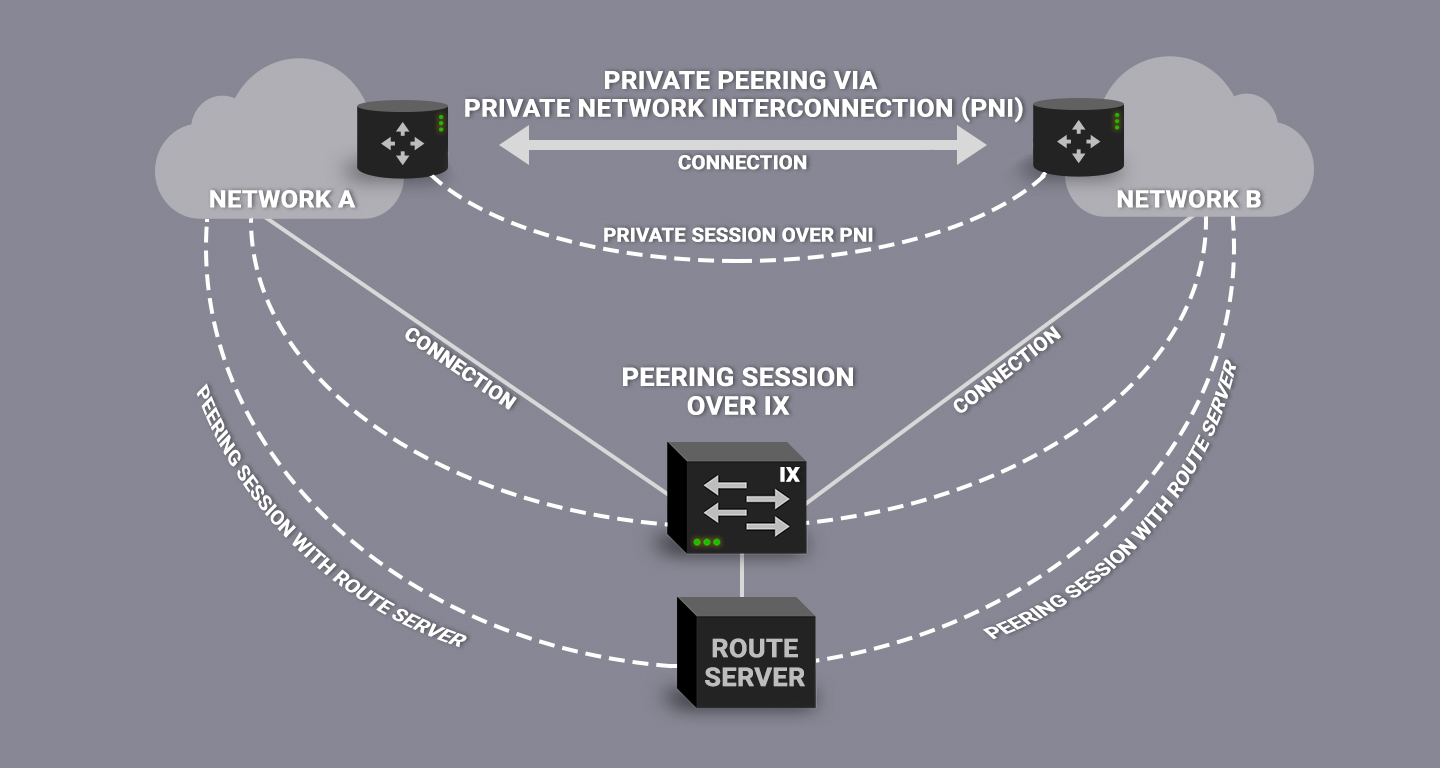

There are several types of peering connection. Peering just means that two networks connect somehow. This could involve running a circuit across town from one network’s facility to the other’s. However, that arrangement requires covering the cost of a metro circuit between the peers. With a lot of peers, that would get expensive fast.

Public peering, done through an Internet exchange, is more common and more efficient. An Internet exchange is an Ethernet switch (or set of Ethernet switches) in a colocation facility, which all the networks peering in the facility connect to. Using an Internet exchange, a network can peer with many other networks through a single connection. Peering arrangements still need to be negotiated with each peer, but no new cabling needs to be done.

Private peering within a colocation facility combines the two approaches. Two networks put routers in the same building, but run a direct cable between them rather than connecting via the exchange point switch. This is most useful when the networks are exchanging a large volume of traffic, which won’t fit on a shared connection to an exchange point. This is sometimes done when the networks are exchanging a large volume of traffic, which won’t fit on a shared connection to an exchange point.

There are also several types of peering arrangement.

Under the usual definition of peering, the networks exchange all traffic from any of their customers to any of the other’s, any where in the network. A variant of this is for networks to exchange traffic only between certain customers, generally customers in a certain region. For instance, a global network peering with a local Swedish network might use the peering session only for traffic from and to its Swedish customers. This would relieve them of the burden of having to haul traffic all over the world to the Swedish network, when the Swedish network wasn’t doing the same for them. This is known as partial or regional peering.

Another variant is what’s sometimes called “paid peering”, also known as “partial transit.” This looks to those outside just like a regular peering session, but one network pays the other to participate in the arrangement. This is done when one network values the arrangement more than the other does. This is normally something arranged between the two networks, and not something an exchange point intervenes in.

Requirements for peering

There are several things you need in order to start peering. The first is a connection to an exchange point. This may involve installing a router in the exchange point’s building, or may involve a metro Ethernet circuit connecting equipment in one of your existing facilities to the exchange point switch. You may need to pay the exchange operator for the switch port, the colocation provider for space, and metro Ethernet provider for connectivity. If connecting to the exchange point using a new router, rather than an extra port on an existing one, you may need to buy a router.

You will need somebody to manage your peering for you. They need to figure out which networks you should be peering with, contact those networks, and make arrangements. Sometimes that means sending email, and sometimes it involves making phone calls or seeking out other network operators’ employees in person. Many peering arrangements are facilitated through face-to-face meetings so if you can, make sure to go to the peering forums and the IXP meetings. Some networks will say yes or no without much discussion, but in some cases you may need to explain how much traffic is being exchanged between your network and theirs, and why peering would benefit them.

You will also need to make some decisions about your own peering policy. Will you peer with anybody who asks, or will you analyse each request and make case-by-case decisions?

Route servers

Netnod operates route servers at its Stockholm and Copenhagen Internet Exchanges. A route server facilitates the administration of peering arrangements for networks present at an exchange point. By connecting to the route server, you can replace some or all of your separate BGP sessions to your peers with one single session towards the route server. Not only does a route server make it easier for networks to manage their peering arrangements, but it also makes it easier for new peers to start exchanging traffic at the exchange point, from day one.

What’s right for you?

Whether peering is right for you will depend on several factors.

Some of them have to do with economics. How much traffic do you have? How much are you paying for transit? How much of that traffic could be easily shifted to peering? How much will peering cost, including the connectivity and people to manage it? Will it save you money? These costs are easy to put into a spreadsheet and see how they stack up for you.

Then there are the less quantifiable, but equally important factors:

How much control do you want over your traffic? Do you prefer hands-on involvement in your traffic routing, or is that something you’d rather let somebody else handle? Does your network have any requirements that the available transit providers can’t deal well with? Is speed and latency important for you? Is keeping traffic local a priority for you? Is the robustness, stability and efficiency an exchange point offers important to you?

If the benefits stack up favourably, peering may be the right thing to do.